The Association Committee “Ad Pacem servandam” held its peace march this year in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The aim of the march was to attend important war sites from World War II and the Bosnian War (1992-1995) to see if the consequences of these wars can still be felt today.

After spending several days trekking in unique mountainous terrain, we visited war museums and monuments in Mostar and Sarajevo. During meetings with representatives of the religious communities we learned how difficult their coexistence is today. The wounds of the Bosnian wars are not yet healed. In Jablanica we also had the opportunity to learn about the aftermath of the Battle of Neretva.

The peace march

We had plenty of time to appreciate the beauty of the surrounding nature and the freedom in the mountains. We considered ourselves fortunate to be able to fully enjoy such freedoms in these restrictive Covid times. We were able to reflect and exchange our thoughts on people who are still in a bad situation because of the wars that happened here, in Bosnia.

Jablanica

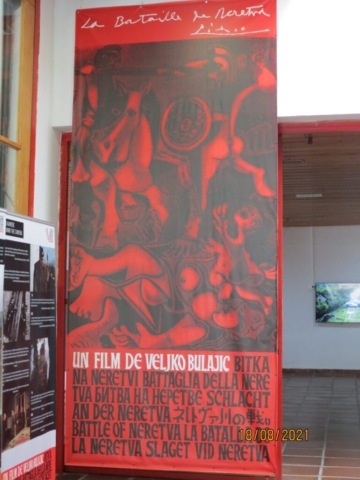

In Jablanica, the first town we visited, it is noticeable how much the cult of Tito has taken root. We felt it above all in the town’s only museum. It celebrates the Battle of Neretva (early 1943), in which Tito’s partisan forces were able to escape the Axis powers across the Neretva River, and ensure the repatriation of the wounded. With the world-famous film “Battle of Neretva” (1968), the then Yugoslav president Josip Broz Tito promoted communist ideals of his country. Pablo Picasso designed the advertising poster for the film.

Tito’s aim was to unite all Yugoslav peoples in a communist state. For this reason, he bloodily suppressed any resistance of ethnic minorities. The forced coexistence of the South Slavic peoples under a communist dictatorship is one of the main reasons for Yugoslavia’s dissolution. It became the main reason for the Bosnian wars back in the 1990s. All oppressed ethnic groups (Slovenes, Croats, Bosnians, Kosovo Albanians, Northern Macedonians) fought against the Serbs, who wanted to prevent the break-up of Yugoslavia by military and means. The war in Bosnia and Herzegovina, that lasted three and a half years, ended with the Dayton Agreement of 21 November 1995, signed by the Presidents of the new states of Serbia, Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

During our visits to Mostar and Sarajevo, we were able to feel the still lingering wounds of this war.

Mostar

During our stay we also heard muezzins calling for prayer from the minarets, as well as church bells ringing. Therefore, mosques, Catholic and Orthodox churches prevail in the cityscape. Religious communities live here side by side, but it is still difficult to establish relations between them.

In conversations with a Serbian Orthodox priest, a Roman Catholic priest and a Hodja (Bosnian name for an imam), we were able to learn that reconciliation and peaceful coexistence remain sensitive subjects. Croatian Catholics, Serbian Orthodox and Bosnian Muslims are now mainly focused on organising and strengthening their own religious communities. There is a lack of opportunities and models for inter-religious cooperation. While many war veterans rather want peace, among young people, as Mostar’s Hoxha explained to us, many (old) ethno-cultural prejudices are becoming more noticeable again.

Sarajevo

Unlike Mostar, the coexistence of religious groups in Sarajevo seems more peaceful. There are fruitful opportunities for exchange and meetings between believers of different religious communities, which in this city include the Jews, whose community in Mostar has broken up.

Sarajevo is a city with a rich history. It was here that Gavrilo Princip, a Serbian nationalist, assassinated Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife Sophia on 28 June 1914. A month later, on 28 July 1914, Austria-Hungary declared war on the Serbs. This date marks the beginning of the First World War.

The consequences of the ethnic wars of 1992-95

Because of the Bosnian war, the composition of the population changed significantly. New data were published only in 2013. They show a drastic change from the last census of 1991, when people could still indicate whether they considered themselves Yugoslavs. In 2013, people had to decide and write down to which ethnic group they thought they belonged. The result was the following data for Bosnia-Herzegovina: 50.11% said they were Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims), 30.78% Serbs, 15.43% Croats and 2.73% identify themselves as belonging to other minorities or do not consider themselves to belong to any of them.

In the city of Sarajevo, the proportion of Bosniaks is up to 80.74%, while Serbs account for just under 4% and Croats for about 5% of the population. About 10% of people stated they did not belong to any ethnic group, or simply called themselves Bosniaks. In Mostar, Croats make up 48.5% and Bosniaks 44%. (All figures are taken from Analisa Bruni, Sarajevo e Mostar pocket, lonely planet u. EDT srl, Turin, 2019, p.19)

The origin of the Bosnian nationality goes back to Tito’s time, when in 1968 this nationality was chosen to denote the descendants of the southern Slavs who adhere to Islam.

From our conversations, we learned that most Bosnian Muslims adhere to a tolerant Islam.

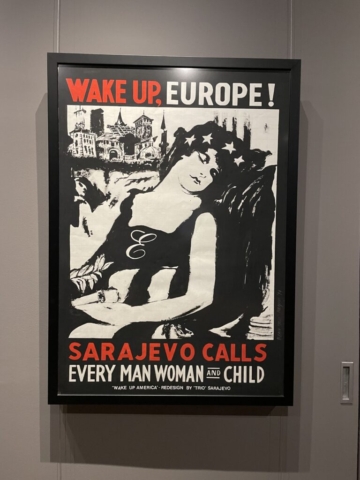

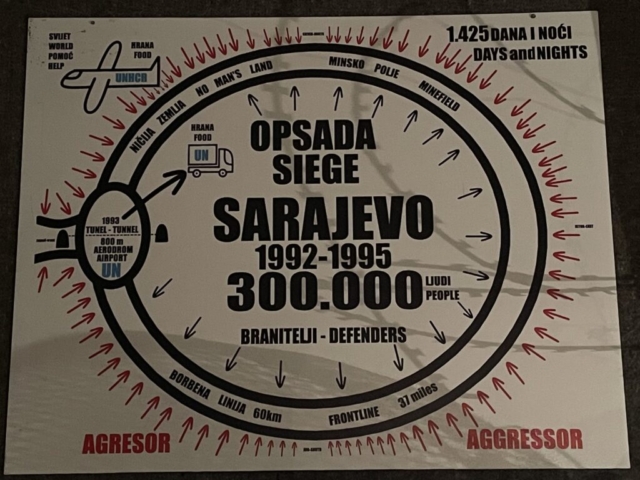

The siege of Sarajevo by the Yugoslav People’s Army began on 4 April 1992 and ended 1,425 days later. The population was cut off from the outside world and initially could only be supplied by air. Later, an underground tunnel was built to provide communication with the outside world. Leaving the houses at that time could have been deadly, as snipers were stationed everywhere in the hilly surroundings of Sarajevo.

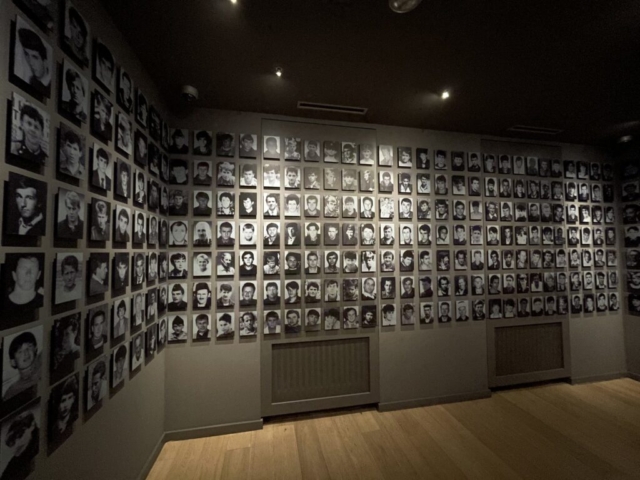

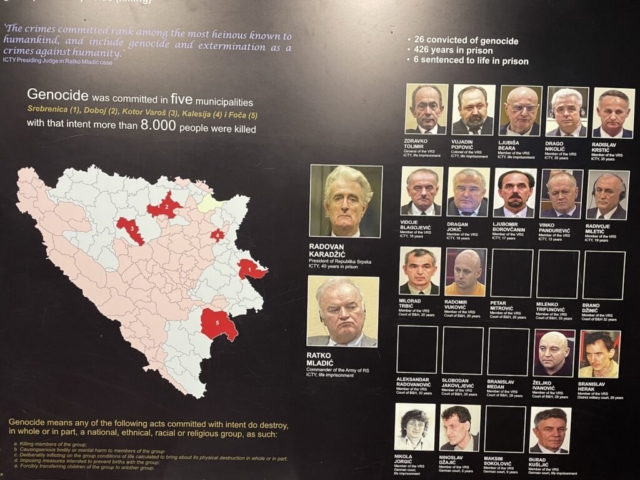

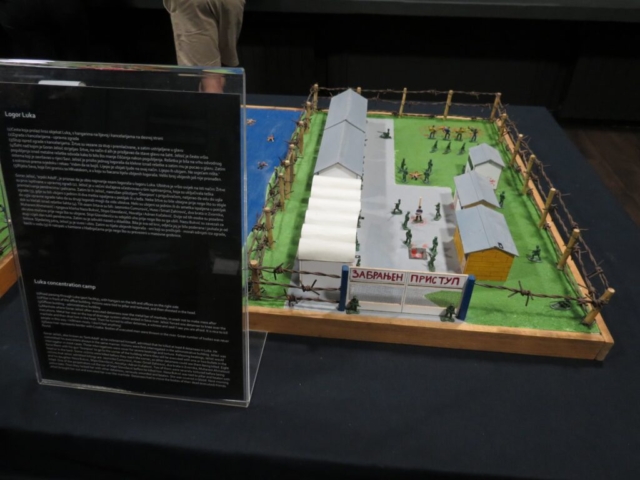

One part of Gallery 11/07/95, Sarajevo Museum, shows everyday life in the besieged city through video clips. In those days suffering and hope were very close together. A large part of the exhibition is dedicated to the ethnic cleansing in Srebrenica. Here, between 11 and 19 July 1995, fighters of the Republika Srpska Serb army brutally murdered 8,000 Bosnian males. Women and girls were raped.

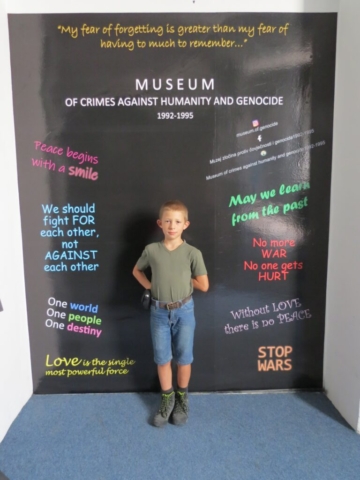

Still, most of the victims are remaining silent because many perpetrators live free and maintain their influence. A visit to the “Museum of Crimes Against Humanity and Genocide” tells of all these atrocities and shows the individual fates in detail. Monuments scattered throughout the city also commemorate these acts. During our visit to the city we repeatedly encountered the so-called “Sarajevo roses”. Bullet holes filled with red paint.

The city is called (to this day) the European Jerusalem because the main religious communities live here side by side and the East and West come together in this city. However, as explained above, today 80% of Sarajevo’s population is Muslim and therefore this designation is no longer accurate.

The influence of the past Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires can be seen in the architecture of mosques, synagogues and churches of various Christian denominations.

The rather timid efforts of the various religions to promote dialogue and encounter are striking. After all, it is common knowledge that there can be no peace in society without peace between the religions in the Balkans.